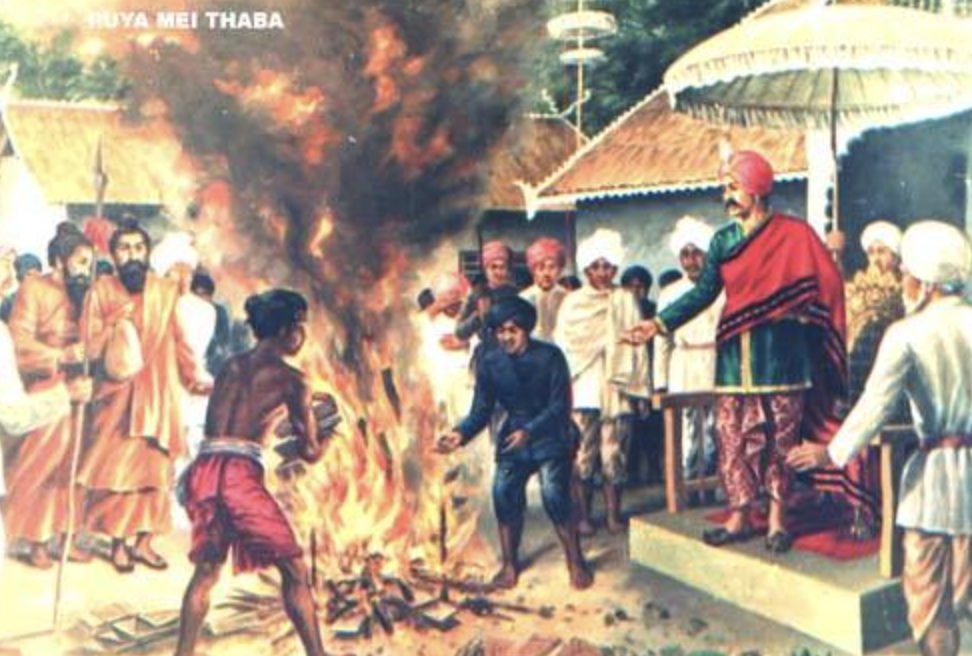

‘Puya mei thaba’ :: Pix Source – Facebook Sanamahism laining.

[Source Wikipedia]

Puya Mei Thaba (Meitei: ꯄꯨꯌꯥ ꯃꯩ ꯊꯥꯕ) (literally, the burning of puya) was a historical event of the burning of the sacred scriptures (puyas) of Sanamahism, the ancient Meitei faith under the tyrannical orders of Emperor Pamheiba on the 23rd day of the Manipuri lunar month of Wakching in 1729 AD in front of the Uttra Sanglen inside the Kangla Palace of Manipur kingdom. It was regarded as the gateway event for the Brahmanical invasion into the Manipuri society.

The historic event of the destruction of the antique scriptures is commemorated still today as “Puya Mei Thaba Numit”. It is observed in different parts of Manipuri dominant regions, especially in Manipur.

[Source e-pao.net, by Dr. Lokendra Arambam]

The following article, sourced from e-pao.net, has been shared here to raise awareness among the citizens of Manipur. It serves as an important resource to keep the community informed and educated on key matters. Sharing information like this ensures that residents of Manipur stay updated, better equipped to handle various situations, and fosters a well-informed society. By using trusted sources, we aim to contribute to the collective knowledge and safety of our people.

‘Puya mei thaba’ : 284th Observation at Kangla, Imphal on 4 February 2013 :: Pix – Deepak Oinam

The indigenous civilization the Manipuris developed throughout its history had a cataclysmic rupture in the early eighteenth century when the emerging world religion of Hinduism was enforced unto the unwilling Meitei population through the use of state power and violence. The burning of the sacred scriptures of the Meitei religion known later as ‘Puya Meithaba‘ became a symbolic site for ideological and national reconstruction from the supporters of the indigenous non-Hindu religion (later termed Sanamahee worship), with profound impact on the social, political and cultural history of Manipur.

The event of state intervention to adopt Ramandi as the official religion of the state, the desecration of native temples of the Umanglais, the oppression of the people in the wake of the conversion of the Meitei people into Hinduism, and the symbolic destruction of indigenous knowledge and philosophy, and forcible assimilation into the new structures and mores of the world civilization of Hindudom had ramifications in the later history of the Manipuri people.

The events of the early eighteenth century had such impact on the historical experience of the people of Manipur that later movements for cultural identity and liberation struggles of the future non-state actors were solidly based on the rejection of the hegemonic intrusion of this world civilization, the Indianizing manouvres of the Brahmin classes newly emerging in the social structure, and behavioural and intersticial changes in social norms, practices and ritual forms ushered in through state power, thereby marginalizing non-Hindu faith and belief. All these were targets of attack and historical revenge by emergent non-state actors, who would seek a profound transformation of Manipur’s culture based on the simple strength, ingenuity and energy of the indigenous faith itself.

To have an objective, detached assessment of the events of the eighteenth century, and to describe the historicity of the minute events, and read into the minds of the persona, individuals, groups, institutions interacting in the tumultous periods in the nation formation of the Manipur people would have been a proper exercise for any student of history and culture. Though the noted historian Fustel de Coulanges had remarked. ‘We must judge the ancients in the light of their ideas and not ours’, we cannot but empathize with the present users of historical imagination to retrieve and re-invent ‘the usable past’ (Van Wyck Brook 1986) thereby ‘obviating the possibility of innocent history, but not the possibility of authentic history when it is actively imagined by its users.

What is deemed usable is valuable, what is valuable is constituted according to specific cultural and personal needs and desires’ (Lois Parkinson Zamora 1997). Therefore, the use of the past event as a metaphor of contemporary struggle for resurgence and nation-remaking exercise is validated by the nature of emotions, passions and struggle involved in the past encounter between two civilizations – Indian and Meitei, and its reinterpretation in the light of cultural struggle for self-presentation and selflocation in an era of armed conflict in contemporary times between the Indian state and non-state Meitei fighting for independence.

This dialectical struggle between two civilizations is of profound importance in cultural discourse of the day. Scholars are of different viewpoints however, standing in binary dimensions of the divide. Some are of the positive character of Manipur civilization in the light of the synthesis between Indian and Manipur cultures while others are of deep distrust for the hegemonizing, cultural imperialistic hegemony of the Indian civilization over the Manipur people thereby blaming Indian culture for the predicaments of Manipur today.

The burning of the sacred Puyas therefore is not simply an erasement of people’s faith, but a restructuring of the ontological being of an independent people into servile producers of a hybrid personality, reduction of a martial race into creative artists and sycophants. The struggle for liberation of Manipur from ‘Indian occupation’ therefore is not only a political struggle, but also a struggle for cultural self-definition in the wake of profound changes ushered by global forces. Nativism and revivalism is also another label over the non-emancipatory stalwarts of the indigenous faith, while the other hidden, unread discourse is about radical transformation of Manipur’s cultural evolution which should resist, and subvert strong forces of Indianizing elements of the oppressive Indian state.

The words ‘Indian’ and ‘Indianization’ are often used freely in the proposed reinterpretation of the cultural process. Many scholars of the near-recent past however preferred the concept of ‘Sanskritization’ and ‘Conversion of the Manipur people into Hinduism’ (G. Kamei, 1991). They would rather not use the word ‘Indian’ since this terminology rather became popular after colonial rule, though the Indie civilization and its corruption from etymological origins of Persian knowledge of the Hindu civilization are well known precepts.

The word Sanskritization is avoided by this author, since, according to the formulator of this concept M.N. Srinivas, it rather meant a process of transformation of an indigenous society through the adoption of Sanskritic culture, yet with an attempt at upward mobility of that society or class or caste through emulation of a culture of a higher caste as a reference point (M.N. Srinivas 1956).

The author would rather explain the internal transformation of Meitei society rather as an indigenous dynamic without a reference point of the higher culture elsewhere, and there was no massive re-orientation of social and cultural forms as is seen in Hindu-Meitei society today. Nor would the author use the term Hinduization of Meitei, but rather Meeteization of Hinduism as a concept on the strength of the indigenous culture itself, which did not indicate a total surrender of the society to the higher religion, but used the higher culture for indigenous needs of the day.

Before entering into this contemporary cultural discourse, it is apt to go back to the event in the early eighteenth century and refresh ourselves with the unfolding of the events and ask questions which might inform the processes of the historical dialectic and its development. A glance at the royal chronicles Cheitharol Kumbaba informs us that the accession to the throne by Meidingu Mayamba (alias Pamheiba) succeeding his father was in 1709 as a twenty year old.

He became king at a certain point in Asiatic history, when nation states in South and Southeast Asia were in a period of great upheaval. In Southeast Asia, the new age was universally one of growth and expansion. The concomitant expansion of territorial frontiers, administrative control and economic activity was unprecedented. During the process, the rough outlines and the cultural and ethnic structuring of the future nation-states were imperceptibly settled.

The pre-occupation of both indigenous and colonial authorities (European empire builders in Southeast Asia) was primarily with the procurement of security and the management of scarce material and manpower resources for increased productivity and profit. Fulfillment of these aims was through the diverse methods of armed control, ideology, administrative ordering and improved communication. In the process, the Southeast Asian community moved into a period of transition leading into the modern era (Cambridge History of South East Asia, ed Nicholas Terling 1992).

Pamheiba, alias Garibniwaz was however a pre-modern ruler who unleashed the forces of Manipur’s energy thereby leaving the imprint of a great nation-builder and mover of the history of the Meitei nation into an empire, though his cultural and religious predilections led to a critical cleavage in society and polity after his death. The transformation effected by his grandson Chingthangkhomba in the organization of the ethno-state was to become unique in Southeast Asian history.

Pamheiba, under unobstrusive, matter of fact entries in the chronicle, organized rituals of his dead father under indigenous norms, took care of the sick and poor by distributing paddy, sitting at an obvious theatrical out house (Khunjaoba Shang) along with his chief queen, went out into the realms of monarchical pleasure trips in villages and settlements (public relation exercises), sent out regular internal expeditions to bring recalcitrant tribes into order through his loyal colleagues and military officials, and organized innovations in the palatial structures and constructions, and entered into the ear-piercing ceremony at the age of twenty two.

Regular boat races were public display of monarchical power in the months of August, and the impact of movements of tribes and communities were often regulated through physical action and punitive punishments. Coronation rites were exemplified through waging of war against tribes too. Frontier posts were often inspected through regular trips, and the ethnic communities at the periphery were assimilated, pacified for retention of the plural order, and the threat from the eastern and western frontiers were kept under surveillance.

For the next few months were to reveal hitherto unrevealed forces of great confrontations amongst the nations, of which the ceaseless confrontations with the Myanmarese and the Bodos of Tripura etc. were to engage the historical energy of the Manipur people. Pamheiba’s military planning, construction of dykes and walls for defensive purposes and relentless aggressive moves with the swift cavalries for raids into enemy territory were to leave powerful markers in the national imagination of the Manipuri.

For the eighteenth century was indeed a period of martial confrontation, and war was an accepted value system. Mass cremations of the dead in the conflict with extra-territorial enemies were the norm. Women did not weep or cry over the loss of husbands, which lent dignity to their personality. Married women could sometimes be enlisted by force into the royal harem, for which later moral guardians cast aspersion to the king (Gomati episode). Death by wives through the practice of Sati (after the conversion) were even ritualized easily, which however was reverted through core civilizational objections.

What was important at that age was that the social energy of the people was moving forward into a period of great vitality and conflictual dynamism, which were met with deep grandeur, grace and capability of sacrifice! The martial race reached its zenith of splendour, and new demands were met on the aspirations for greatness, power and exuberance by the collective labour of the people. Why did the monarch then ushered in a period of mutual antimony, rupture and cleavage in society, and what were its effects remain a feature of great concern to students of history and culture today.

Simple entries by Cheitharol Kumbaba reflects the nature of intellectual and cultural transactions that were taking place in the corridors of power in the medieval state. Arrivals of Brahmin priestly classes were regular features since the fifteenth century, and conversion of the kings in different sects in the interpretation of Hinduism were often achieved through labourious processes of court intrigue, and favourable kitchen influences from the harem.

Open debates at the Pongbeipham (native Darbar) were regular features, and the native intellectual tradition led by the wisdom teacher Lourembam Khongnangthaba was at the height of its maturity and fulfillments through production of indigenous knowledge for more than a hundred years since the days of Khagemba (1606-1652 AD). The extent of production of religious scriptures, the philosophical tenets and ritual systems of the pre- Hindu Sanamahee religion were at its quantum best, and the grace, wisdom, mystic powers and visionaire presence of the wisdom teachers lend to the character of the native civilization a distinct generosity, strength and self-sufficiency of the indigenous culture.

Why then was Pamheiba becoming a sudden enemy of the people? What were the principle motive factors for his lending ears to the so-called ‘insinuations’ of the Tantric priest from Shyllet who reached Imphal in 1716 AD (arrival date is controversial) Santadas Goswami has now become the villain of the drama behind the personal transformation of the monarch, and people at the villages and nooks and corners of the state have become familiar with the intrigues of this priest, through popular dramas and touring theatres since the middle of the twentieth century.

As scholars of culture and religion of Manipur had indicated, Pamheiba was a convert into the newly emerging cult of Shiva worship through one teacher called Gangadhar, probably in the Madhavcharya School of Vaishnavism (M. Kirti 1980), while in 1717 he was converted into the Bairagi Chaitanya School through Gopal Das (G. Kamei 1991). In 1720, Guru Gopal Das returned to his native place and Shanta Das Goswami became the main perceptor and advisor to the king, more forcefully since the twenties of the eighteenth century. Ramandi was introduced as the state cult in 1720 AD.

For Further reading

Part 2, click here

Leave a Reply